Meditation platform

(Amazonica 2023, Iquitos, Peru, )

(Amazonica 2023, Iquitos, Peru, )

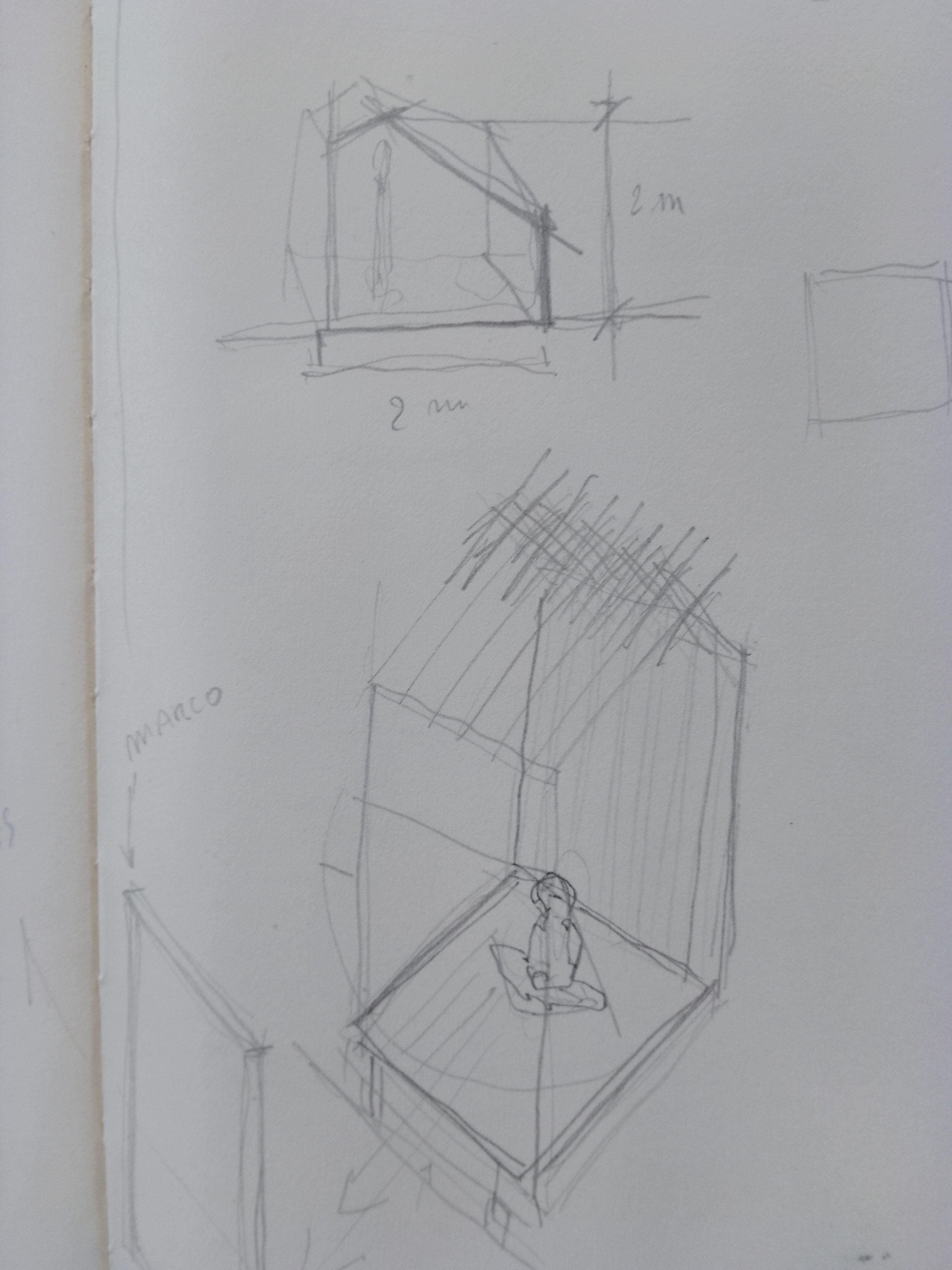

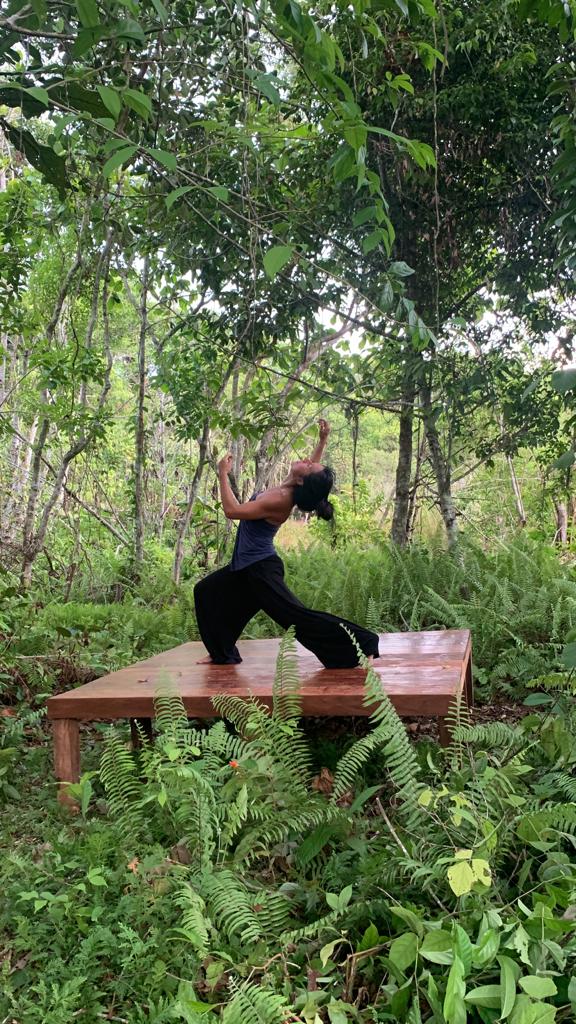

In recent years, as a spiritual researcher and as an artist, I have worked on and questioned the distinction between human beings and what we call 'nature'. I created habitable installations and sculptures, in dialogue with architecture, which could be used, experienced, enjoyed, inducing an experience of fusion and non-separation with the natural environment. During the Amazonica 23 residency - organized by Correlación Contemporanea - I wanted to create a structure to be placed in the natural environment, which would serve as a space for meditation, mediation, reflection and connection with the forest. The encounter with the Shipibo culture and with Maestro Richard Ramírez Pëkon Kuppi added a new level to this initial idea, placing the work in dialogue with the shipibo cosmovision and mythology. The Shipibo are not native to the Iquito area: their traditional territory is the middle and upper reaches of the Ucayali River. Many Shipibo, however, have moved to Iquitos over the years for economic reasons.

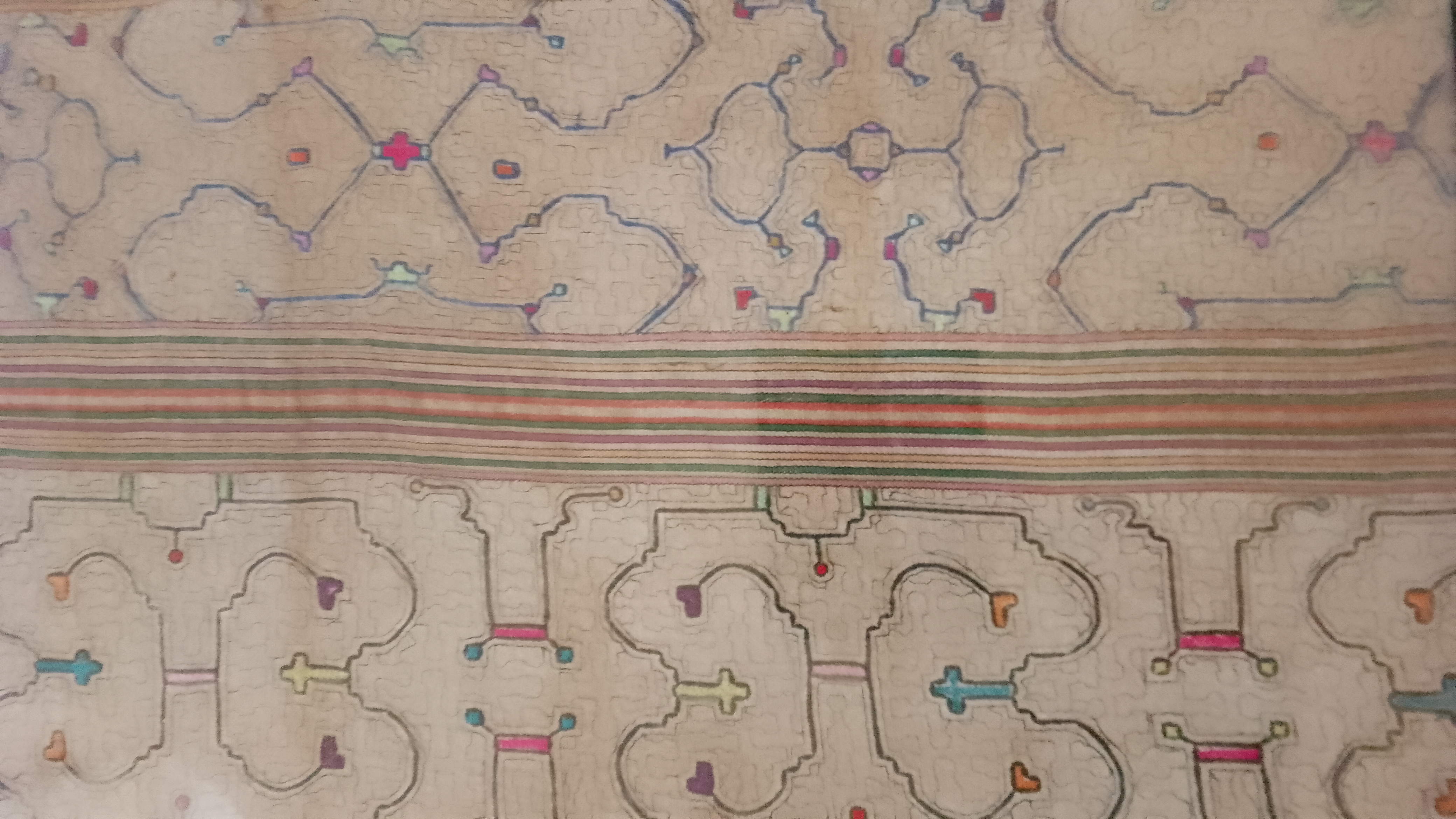

The Shipibo are famous for their graphic art, for the designs that cover ceramic artifacts and textiles. These geometric designs, which in Shipibo are called kené, have a particularly important role. According to Shipibos, in mythical times, the sky, forests, people and animals were covered with a continuous network of these designs. According to the myth, the wisdom of the drawings belongs to Ronin, The Great Boa of the World, on whose skin all the drawings are collected: “In the beginning a giant anaconda lived in the darkness. She began to sing the drawings on her body, and the drawings fell from her mouth into her songs. The drawings came together and took shape, creating the universe and the Shipibo". In mythical times, therefore, a network of drawings united humans and everything else, plants, animals, sky and earth. A mythical time of union. Due to the errors of human beings, this sublime union of geometric features broke and the world was divided into three planes superimposed on each other: the world of the sky, the world of the earth, and the world submerged under the water . This world of separation is the world we live in today.

During the ceremonies carried out by Shipibo shamans, this mythical time comes back present and experienced. The ceremonies and healing process are guided by the songs of the shamans, called icaros. There is a direct relationship between the icaros and the kené, between the songs and the geometric designs. The drawings are the graphic expression of the songs, like a notation system, which makes the singing visible, and makes the drawing audible. The network that unites the world in a spiritual unity to which the shaman has access and which is revealed to the patient through the visions of ayahuasca, has its own sound. The songs are the drawings, and they operate on the drawings. For the Shipibo the universe is made of music, and everything in it has a specific drawing that can be sung. Ayahuasca allows Shipibo through their visions to see and connect with the world of drawings and songs around them.

The shaman is a master of the icaros, and has the gift and ability to sing and see the designs that make up the universe. During the ceremonies the shaman guides the patient on his spiritual and healing journey through singing, dialogues with the strength of the master plant while acting on the patient's body and psyche. In accordance with the needs revealed in the ceremony, the shaman inscribes, by chanting, in his patient's body the appropriate kené for his healing.

Under the guidance of maestro Richard, I also participated in ayahuasca ceremonies during the artistic residency. My work is indeed the result of the knowledge of the Shipibo worldview I acquired, but it is also the result of the personal encounter with the master plant.

I reproduced an intricate shipibo drawing on the meditation platform I built. Whoever uses the sculpture, sitting at its center, finds herself surrounded and supported by this network of drawings, up to the edge of the structure, which then extends into the multifaceted universe of the forest. The kené connect those who sit on the platform with the natural world around them, evoking the mythical dimension of union.

Regarding the materials used: employing wood to build in the Peruvian Amazon, an area affected by illegal trafficking of valuable wood, requires caution. The use of unauthorized wood for construction, even locally, is widespread. Through the Peruvian Ministry of Production I came into contact with sawmills which - I was assured - buy wood legally extracted from the forest, in accordance with the rules of sustainable exploitation of the forest ecosystem.

Also regarding the materials: building with wood in the forest means surrendering to the inevitable impermanence of our work. Even with the necessary precautions and the use of natural products to protect the material, the wood will sooner or later be reintegrated into the life cycle of the forest, broken down by termites, fungi and torrential rains. I consider this aspect an integral part of my work, and I think with serenity about this process of reintegration of the final components of my installation into the life cycle of the forest itself. Ultimately, this is precisely what I am interested in communicating.

The sculpture enabled a creative collaboration with Roxana Barba, also a resident of Amazonica 23, who improvised a performance/choreography inspired by Shipibo drawings and performed in the forest on the sculpture itself.